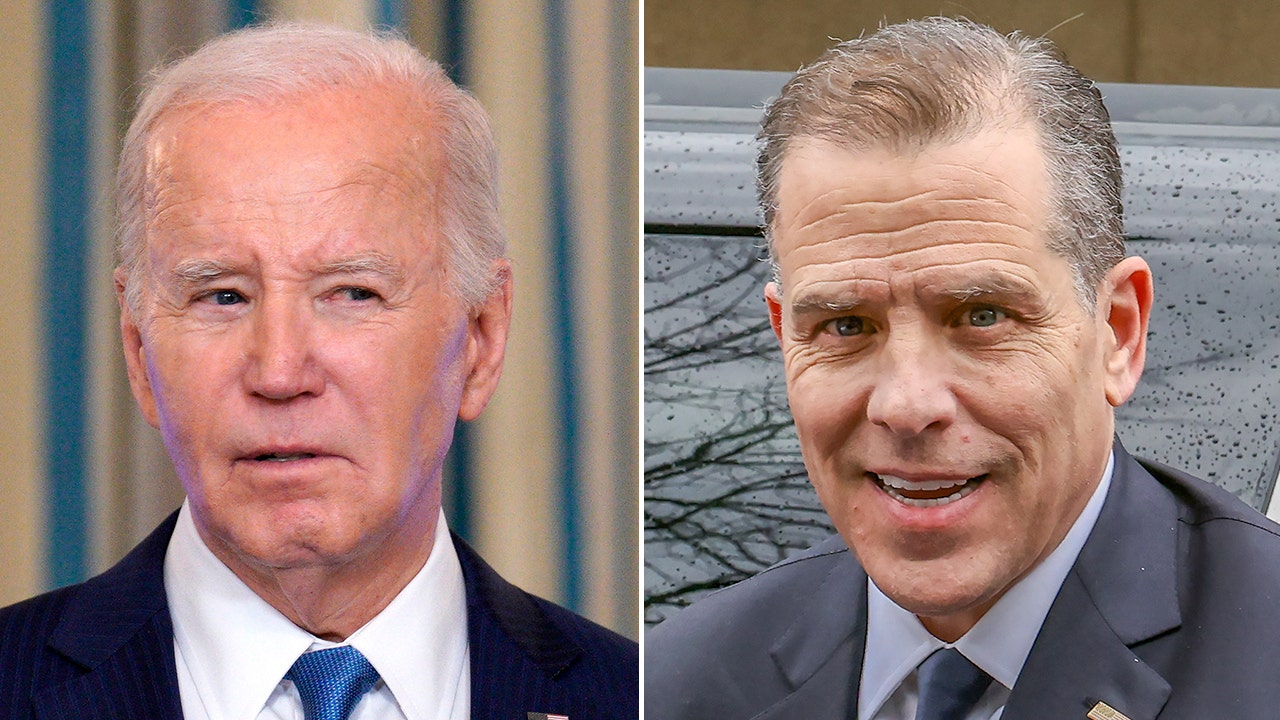

A couple ads in between, but super funny

This is one of the best ones we've seen

https://rumble.com/v555xtt-epic-parody-video-goes-viral-after-biden-crashes-and-burns-at-debate.html?mref=22lbp&mc=56yab

This is one of the best ones we've seen

https://rumble.com/v555xtt-epic-parody-video-goes-viral-after-biden-crashes-and-burns-at-debate.html?mref=22lbp&mc=56yab