Bruddah IZ

DA

Trade Retaliations Make Your Own Country Worse Off

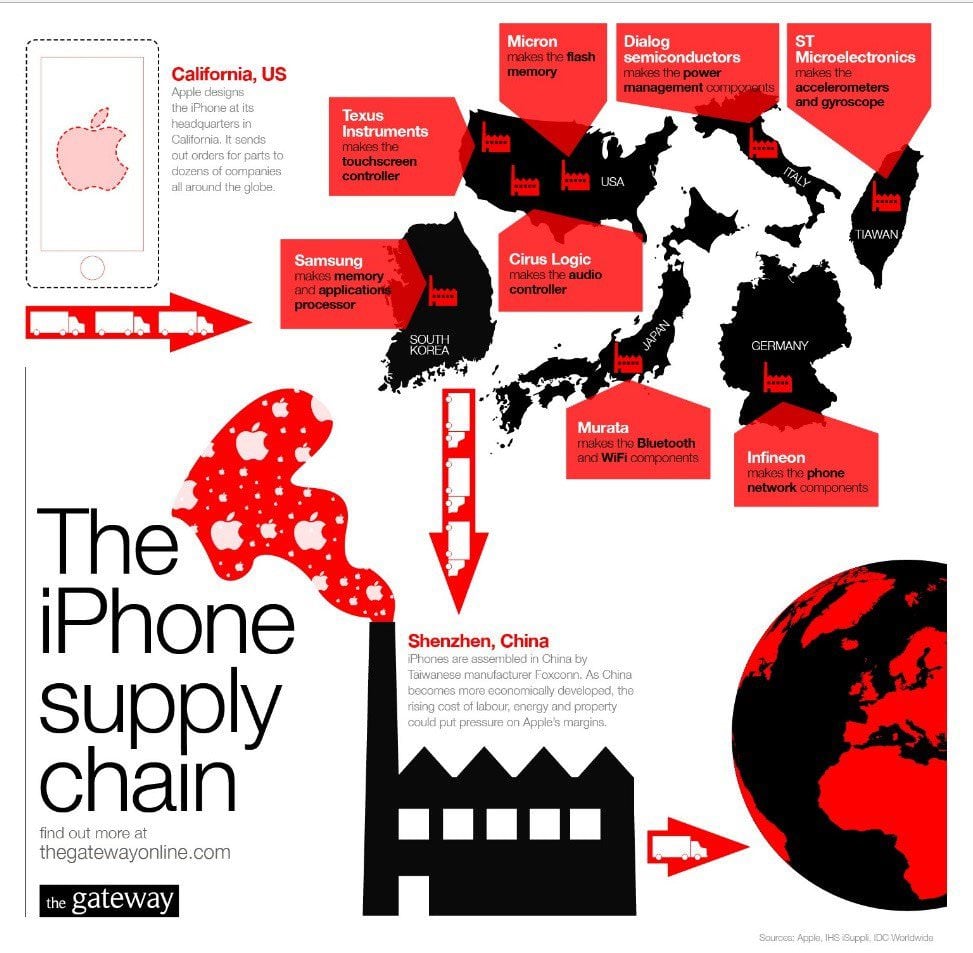

But what about other countries that impose import tariffs against our goods to “protect” their own industries and employments? Should we not respond with retaliatory tariffs and related import restrictions to teach them a lesson? If we do we only injure ourselves, in so responding to the trade barriers erected by other countries.

A British economist, Henry Dunning MacLeod, gave a vivid reply to the argument for a retaliatory tariff back in 1896. He said:

“By the method of retaliatory duties, when the [other country] smites us on one cheek, we immediately hit ourselves an extremely hard slap on the other. [The other country by its import duties] does us an injury, and we, by retaliating, immediately do ourselves a great deal more. The true way to fight hostile tariffs is by free trade.”

Retaliating with counter tariffs merely makes the goods previously purchased from the foreign country more expensive for the consumers of your own country, lowering their standard of living through higher prices and a smaller variety of goods from which to choose. And by reducing the sales earned by the foreign producer in your country, he has less revenue from which to buy your country’s exports, with a negative effect on those sectors of your own economy.

But what about other countries that impose import tariffs against our goods to “protect” their own industries and employments? Should we not respond with retaliatory tariffs and related import restrictions to teach them a lesson? If we do we only injure ourselves, in so responding to the trade barriers erected by other countries.

A British economist, Henry Dunning MacLeod, gave a vivid reply to the argument for a retaliatory tariff back in 1896. He said:

“By the method of retaliatory duties, when the [other country] smites us on one cheek, we immediately hit ourselves an extremely hard slap on the other. [The other country by its import duties] does us an injury, and we, by retaliating, immediately do ourselves a great deal more. The true way to fight hostile tariffs is by free trade.”

Retaliating with counter tariffs merely makes the goods previously purchased from the foreign country more expensive for the consumers of your own country, lowering their standard of living through higher prices and a smaller variety of goods from which to choose. And by reducing the sales earned by the foreign producer in your country, he has less revenue from which to buy your country’s exports, with a negative effect on those sectors of your own economy.